From Bananas to Bivalves: Selective Breeding for Oyster Resilience

BY Alexa Osuna-Fernandez

Bananas.

I bet that you, my reader, have seen a banana before, those yellow curved fruits often associated with monkeys. Bananas, as we commonly know them, are a result of about a thousand years of selective breeding. Selective breeding has made bananas a human favorite by minimizing the number of seeds in them and making them larger, improving the product quality. Just like our yummy, cultivated bananas, oysters are also being selectively bred. Oyster breeding has only recently commenced in the past century as a response to the declining stocks due to disease, climate unpredictability, and over-harvesting. This has resulted in triploid oysters that are more resilient to parasites and climate change, produce more meat, aren’t limited to seasonal growth, and develop at faster rates; in turn, they are aiding the economy and sustainability efforts of coastal communities.

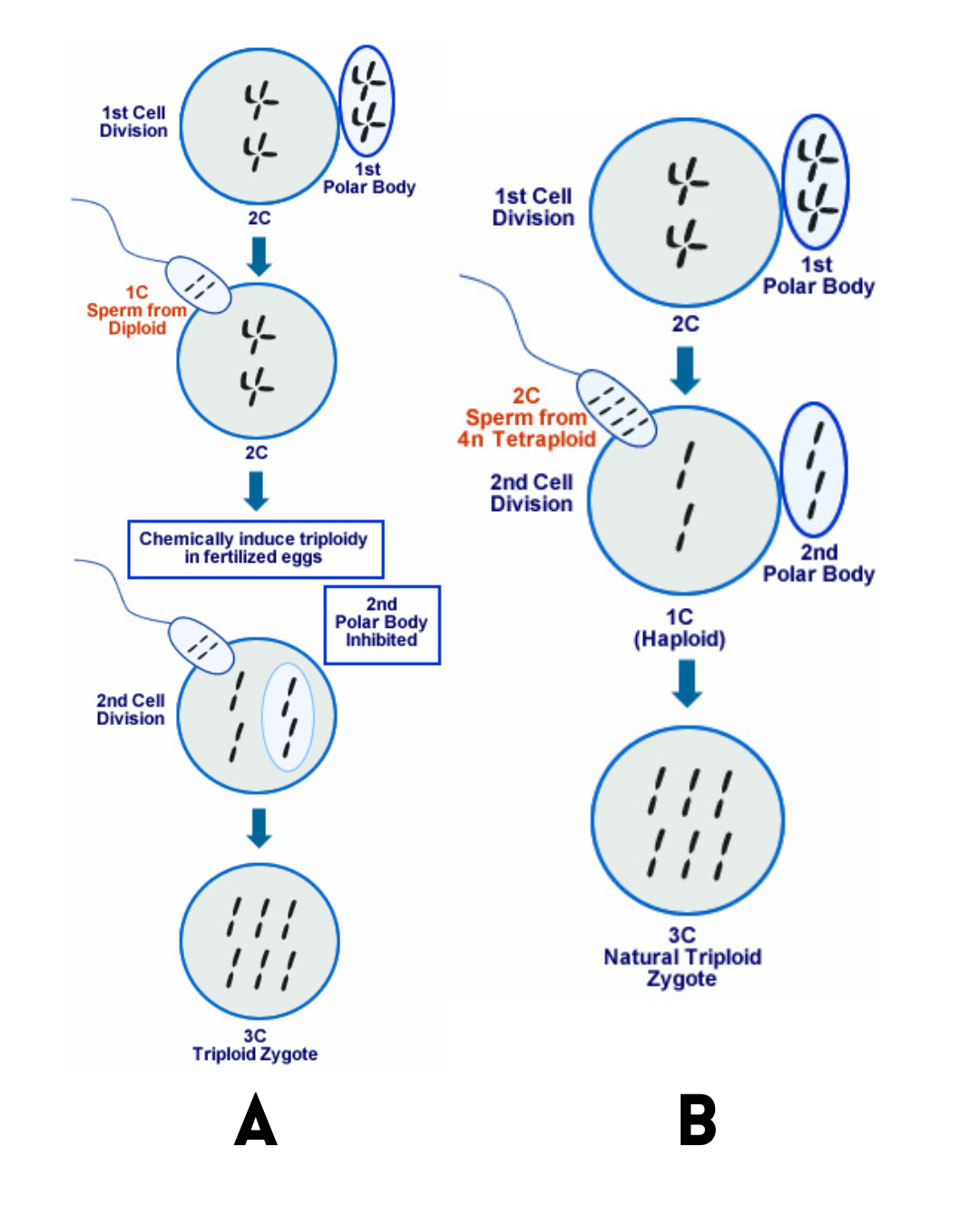

Figure 1. Chemically induced creation of a tetraploid to generate a triploid offspring.

What Happened?

First things first, selective breeding is not the same as genetically modified. Genetic modification can happen in three different ways: recombining DNA by incorporating nucleic acid molecules from one organism into another, directly injecting DNA information into a different organism that isn’t the supplier, or by protoplasmic cell fusion. Selective breeding is a simpler process that does not require molecular engineering methods; instead, it involves obtaining a male and female with the most desirable traits to reproduce. Selective breeding is conducted continuously until the offspring possess the desired target characteristics.

Naturally occurring oysters have two sets of chromosomes, diploids (2n), and the selectively bred oysters have three sets of chromosomes, which are triploids (3n). So, how do we get diploids to create triploid offspring? We don’t, well, at least we don’t use two of them. The first step is to induce a diploid to produce a tetraploid (an oyster with four sets of chromosomes, 4n) by either chemically blocking, pressure, or temperature shocking the meiosis process, a method that must be timed perfectly and with very low success rates. Once the tetraploid is created, it can be used to parent triploids. Usually, a male tetraploid (4n) and a female diploid (2n) are coupled to create triploid offspring.

These triploid offspring are considered functionally sterile, which gives them their advantage. When the oysters are sterile, it means they don’t have to use any energy or resources in the most basic function of a living being, reproducing. Therefore, they can expand themselves to grow bigger and faster. In addition, triploids do not typically spawn, so temperature changes that may typically induce a spawning event do not affect them, resulting in more consistent and constant oyster supplies. Using selective breeding, oyster farms have been able to maintain the presence of oysters in waters that may not support their survival year-round, thereby aiding the local ecosystems and local businesses.

What’s happening now?

So, how does this help with coastal ecosystem health? A population decline of up to 99% has been recorded on the Atlantic and Pacific coasts of the United States due to several factors, including climate change, coastal development, pollution, over-harvesting, diseases, and invasive species. It may be hard to believe since many people, including myself, are unaware of just how fundamental oysters are to the coastal ecosystems, but they are a keystone species. Without oysters, coastal ecosystems would erode, literally. There would be a loss of biodiversity due to the lack of habitat, and water quality would decline drastically. They may not be as sexy as coral reefs, but oyster reefs are just as fundamental to shoreline and coastal health.

If selective breeding is successful beyond hatcheries, rebuilding oyster reefs could become a reality. Wild oyster populations could be left exclusively for ecosystem reconstruction, and triploid oysters could remain as harvestable, thereby improving the water quality by scaling production, increasing turnover through rapid growth rates, and meeting supply and demand without disturbing restoration efforts. To emphasize the importance of selectively bred oysters, it is also crucial to highlight the economic benefits the industry could achieve. In the U.S., the oyster industry was estimated to have an impact of over $2 billion in 2019 and generate millions of oysters valued at over $200 million in 2018. This industry has a significant impact ,ranging from job creation to the supply of materials and resources .

Just as bananas have undergone selective breeding to produce the fruit we all know and love, oysters are undergoing their own transformation that reaches beyond kitchen tables. As wild oysters continue to recuperate, selectively bred oysters are giving way to a solution that balances the demand of human consumption and coastal restoration.

meet THE AUTHOR

Alexa Osuna-Fernandez

B.s. From the University of California San Diego & 2025 MIA Summer intern